Polymathy and the Urge to Learn Everything

This explains a lot of my life….

I have a strange urge to learn everything. It’s been that way for as long as I can remember, too. As a child, I often felt odd about it, especially when I learned children weren’t fascinated with, say, radioisotopes or American Civil War historiography. Mind you, I wasn’t particularly amazing at school or was some kind of Isaac Newton genius. I just found the universe to be endlessly interesting and was always on the hunt for new, intriguing questions and discoveries.

As I grew older, this didn’t change, and now I have a newsletter that’s about those things I’m curious about. A good term for this is “polymath”, which Oxford English Dictionary defines as "A person of wide knowledge or learning; a person well-versed in a variety of subjects or skills.”

I would definitely not claim to be at the level of a polymath, but I find the term resonates well. Often, it seems many things in my life start with a simple curiosity and asking questions about why things are the way they are.

As I’ve gained more life experience, I’ve seen how polymathy is not just a quirk but a valuable life skill. Being curious and having a wide range of knowledge is important; here’s why.

Knowledge is most powerful when not siloed.

Knowledge tends to come to us in isolation from other knowledge (or “siloed”). This is a pretty typical way new information is taught and learned, and while that works, the world is in reality more nuanced. Fields of study overlap; new discoveries affect other seemingly unrelated parts of knowledge. The universe we live in is much too complicated for it to be nicely compartmentalized, and learning widely can bring diverse pieces together that would never be noticed otherwise.

Knowledge is a web.

Instead of being compartmentalized, the knowledge humanity has accumulated over thousands of years acts more like a web. Everything there is to learn is related to something else, which is related to something else, and so on. Everything is connected to some other piece of information, and these connections are an important part of the learning process. Information does not exist in isolation.

In an age of information abundance, synthetization of information and knowledge convergence are more important than ever.

When any piece of information can be found with a quick ChatGPT query, those who have a wide range of knowledge forming a base layer of how things are will stand out the most. Done correctly, this can build points of real insight around areas of convergence between what would seemingly be unrelated pieces. If we live in a world where we just pull random pieces of information off the internet when we need it, we won’t have a wide enough knowledge base for the critical functions of discernment and critical thinking. In truth, I think this is one of the greatest dangers of AI: we could rely on it for information to the point we no longer have a solid enough understanding of reality to make proper decisions with adequate critical thinking skills. Indeed, critical thinking may well be the first casualty of a society that grows up on instant answers from (supposedly) super-intelligent computer models.

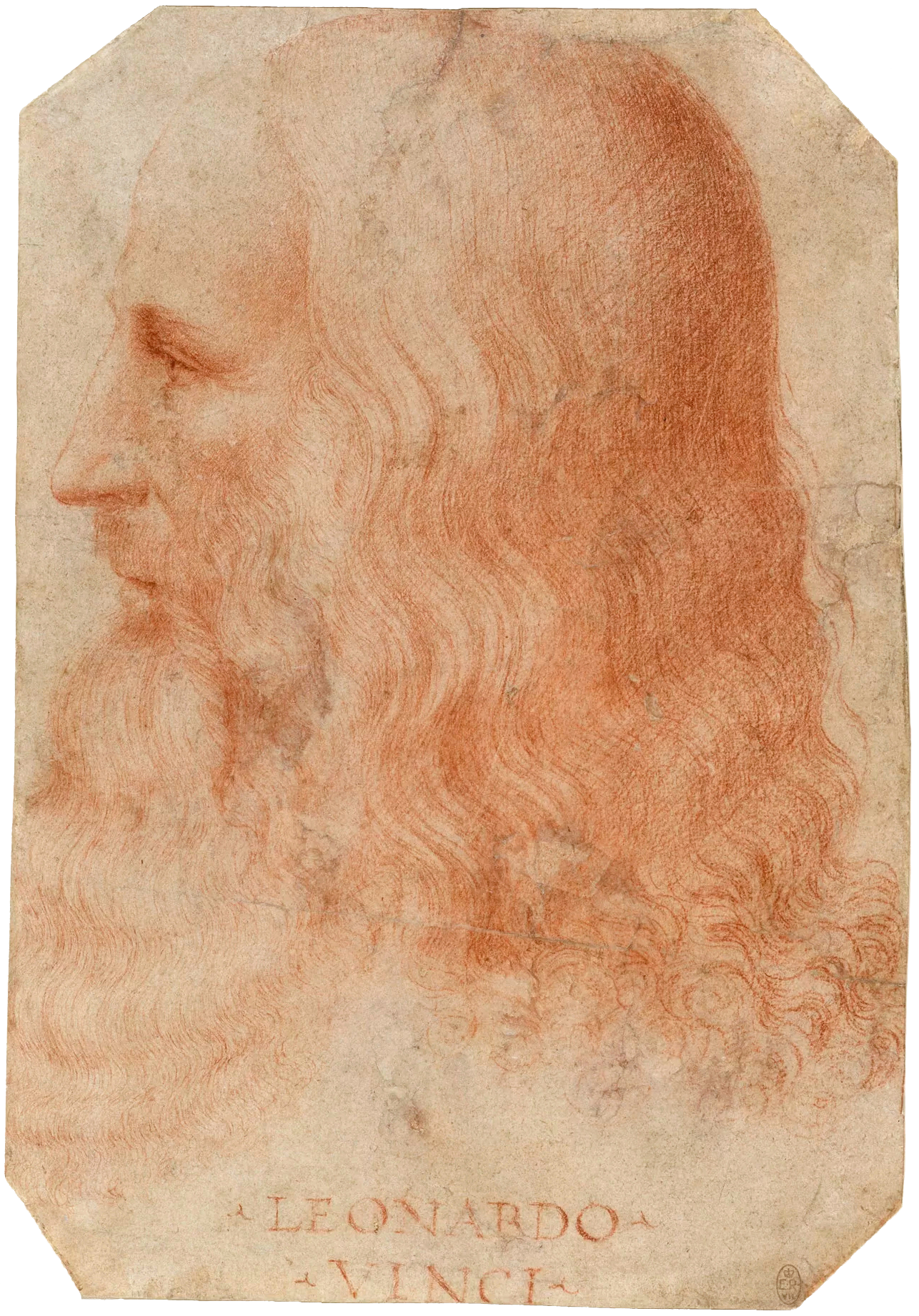

There are some fascinating examples from history of polymaths. Leonardo da Vinci explored a wide range of fields such as art, engineering, anatomy, and mathematics. Or there’s Ben Franklin, who effortlessly moved through the realms of politics, invention, diplomacy, printing, and more. And then there’s Winston Churchill, who served in politics for 40 years, published endless books and speeches, was a bricklayer, painter, won a world war, and was a journalist.

The point is, having a wide range of knowledge is not a distraction; it’s a life asset. And it’s more fun, too. So for those out there, like me, who may feel a bit concerned about your insatiable curiosity about, well, everything - it’s not a bug. It’s a feature. Lean into it. It will serve you well.

Stay curious, Reagan